A Montessori Dictionary: Elementary & Adolescent Terms

As is often the case, specialties or practices have their particular lingo. Montessori is no different! In this Montessori Dictionary post, we’re focusing on a few terms (some familiar, some far from familiar) that apply to the elementary and adolescent years. When possible, we’ve included some quotes from Dr. Maria Montessori. We encourage folks to take a look at her work. Dr. Montessori was a woman well before her time and her books continue to be a source of inspiration!

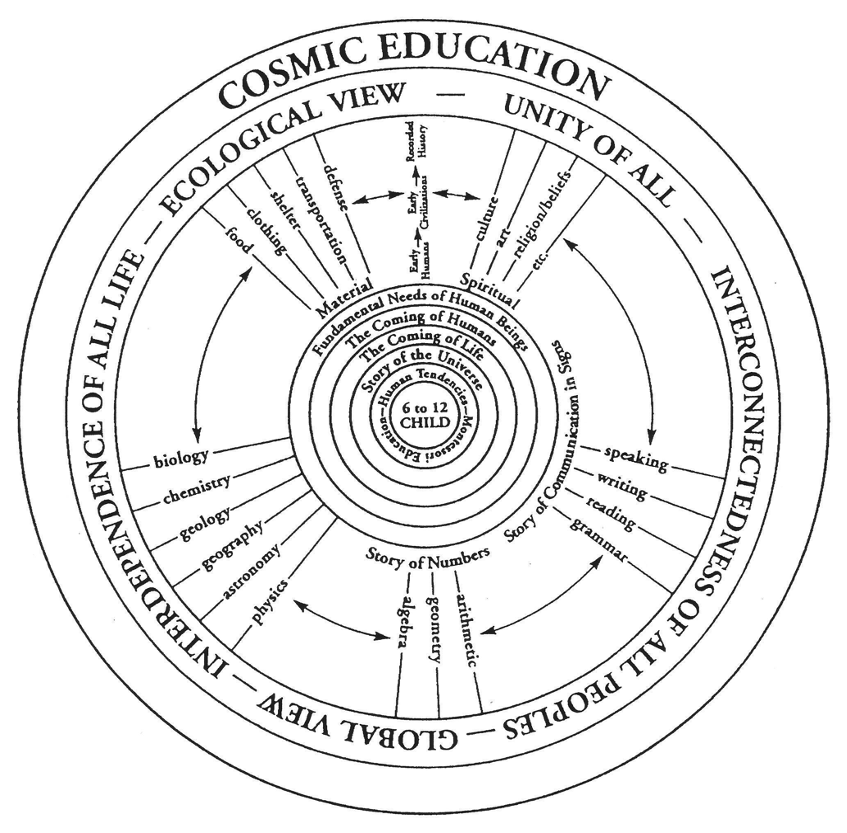

Cosmic Education

“Since it has been seen to be necessary to give so much to the child, let us give him a vision of the whole universe.” –Dr. Maria Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential

Dr. Montessori developed Cosmic Education as an educational approach for children in their elementary years. This approach is based on the needs, tendencies, and characteristics of children ages six to twelve, and provides an awareness of the interconnectedness of all things, as well as a sense that the universe is ordered, governed by rules, and is inspiring. Cosmic Education also provides an understanding that all we know and learn is built upon the great work of those that came before us in the whole of human history.

“If the idea of the universe be presented to the child in the right way, it will do more for him than just arose his interest, for it will create in him admiration and wonder, a feeling loftier than any interest and more satisfying….his intelligence becomes whole and complete because of the vision of the whole that has been presented to him, and his interest spreads to all, for all are linked and have their place in the universe on which his mind is centered.” –Dr. Maria Montessori, To Educate the Human Potential

Erdkinder

Dr. Montessori’s vision for adolescence was to have a land-based program where adolescents can engage in meaningful work that balances intellectual and physical pursuits. This program is ideally a residential farm school in a country setting where adolescents can pursue the real work of the farm and create a community separate from their families. This kind of work allows adolescents to cultivate social and economic independence through valuable experiences in social organization, economic vitality, and intellectual pursuits.

“This means that there is an opportunity to learn both academically and through actual experience what are the elements of social life….We have called these children the ‘Erdkinder’ because they are learning about civilization through its origin in agriculture. They are the ‘land children’.” –Dr. Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence

Imagination

Imagination allows us, as humans, to understand and shape the world in significant ways. Dr. Montessori emphasized that children have great imaginative power that is essential to their self-construction and human development. Imagination is what has allowed humanity to make advances, create, invent, and work through problems that have not yet been solved.

Imagination is the superpower of elementary-age children. They have built up their sensorial experiences and impressions during their early years and are now able to use this foundation to imagine through time and space. Thus, a great deal of the elementary curriculum appeals to the imaginative ability of children ages six to twelve.

Occupations

Occupations are opportunities for adolescents to try on adult-level activities and work that integrates the mind and the body. These experiences are focused and purposeful and allow adolescents to experience how they can contribute to their society. Often adolescents will ask, “What will I use this for?” They deeply want and need to use their knowledge to make an impact in the world. Occupations can range from beekeeping to bookkeeping. They are practical experiences, typically connected to the land or other non-academic pursuits.

Plan of Study and Work

“…the aim should be to widen education instead of restricting it.” –Dr. Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence

At the adolescent level, Montessori education is based on a general, holistic program of study that integrates with work on the land, production and exchange, and support for the developmental needs of adolescents. This general plan includes:

- the moral and physical program that emphasizes how adolescents should be treated as vulnerable growing young humans;

- a syllabus and methods for education, which includes activities and methods for self-expression, cognitive and intellectual development, and preparation for adult life; and

- practical considerations for prepared environments, ways for adolescents to be involved in economies, and varied and supportive adult involvement.

Psycho-Discipline

To understand the term psycho-discipline, it can be helpful to look at the two parts of the word. The prefix, psycho, means relating to the mind or psychology, and comes from the Greek for “breath, soul, and mind.” Discipline is a branch of knowledge. Thus psycho-discipline is the knowledge that is presented according to the psychology of the learner.

In Montessori, we focus first on the whole young person and figure out how to support the characteristics and needs of that individual and where they are in the stages of development. As such, the learner connects to what they are learning because they are naturally engaged with, and own, their process of learning. The learning process ultimately helps the individual’s process of self-construction.

“Education should not limit itself to seeking new methods for a mostly arid transmission of knowledge: its aim must be to give the necessary aid to human development.” –Dr. Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence

If education in the “disciplines” is to aid human development, the focus becomes on the individual and their holistic growth, rather than solely on the content.

Please be sure to schedule a tour of our school so you can see how Montessori education aids human development, inspires the imagination, and gives a vision of the whole universe!

Subscribe to our Blog

You might also like