The Importance of the Kindergarten Year

The Importance of the Kindergarten Year

It’s that time of year again…

Schools and parents alike are planning for next school year. If your child has been in a Montessori class for a year or two, you may be thinking ahead to kindergarten. Many public school systems offer kindergarten, and many parents are curious about this transitional year. This post is meant to highlight the important reasons why a child benefits from that final year in the primary classroom cycle.

Why should your child stay in Montessori for the kindergarten year? Consider the following:

Montessori inspires children

Does your child love school? The aim of Montessori education is not just to deliver information, but to encourage their existing curiosity and wonder. All children are born ready and eager to learn; it is our job to show them how amazing our world is. We want them to ask questions and search for the answers.

If we can give children this gift at a young age we are setting them up for a lifetime of success and happiness.

They will get a chance to practice leadership skills

Most Montessori classrooms host an age span of three years. During the first year or two of the cycle, children are familiarizing themselves with the materials while watching the older children who begin to master their environment.

The third year gives children the opportunity to be role models. They are able to take on more responsibilities in the classroom and often help guide younger students. Kindergartners even give lessons to younger students (which has the added benefit of displaying their mastery of skills.)

Children in Montessori get to work at their own pace

Montessori teachers strive to meet children right where they are, in every area. We truly “follow the child”, giving lessons and guidance according to the individual’s needs, not the needs of the whole class.

Perhaps your child is a strong reader and needs someone to provide them with advanced books that are still appropriate for their age. Montessori teachers have the flexibility to do that. Maybe your child needs a bit more guidance in math. Montessori primary classrooms are structured to include lots of individual and small group lessons, so teachers use that time in whatever ways best meet the needs of each child they serve.

Montessori uses formative assessment, not standardized tests

Children in Montessori classrooms don’t have to worry about high-stakes standardized tests. The english word assess is derived from the latin assidere, which literally means ‘to sit by’. Montessori classrooms rely mainly on formative assessment, a style of gauging student understanding that reflects the original definition of the word.

Formative assessment is done continuously throughout the learning process - even mid-lesson! This allows teachers to adjust instruction in the moment so that learning is constantly tailored to meet children’s needs.

In conventional classrooms, lessons are often firmly defined prior to instruction. The information is delivered to a group of children, and they may later be given a summative assessment to check for their understanding. This data may be used to drive future instruction, or it may just be used to support a grade given on a report.

In classrooms that rely heavily on formative assessment, a teacher can change course while they are in the process of teaching. If students demonstrate prior knowledge or quick understanding, the lesson can be extended and additional information can be included. If children appear to need more support, the teacher can repeat the material or give other supplemental information. Montessori teachers take copious amounts of notes to constantly document these interactions.

The spiraling curriculum comes full cycle

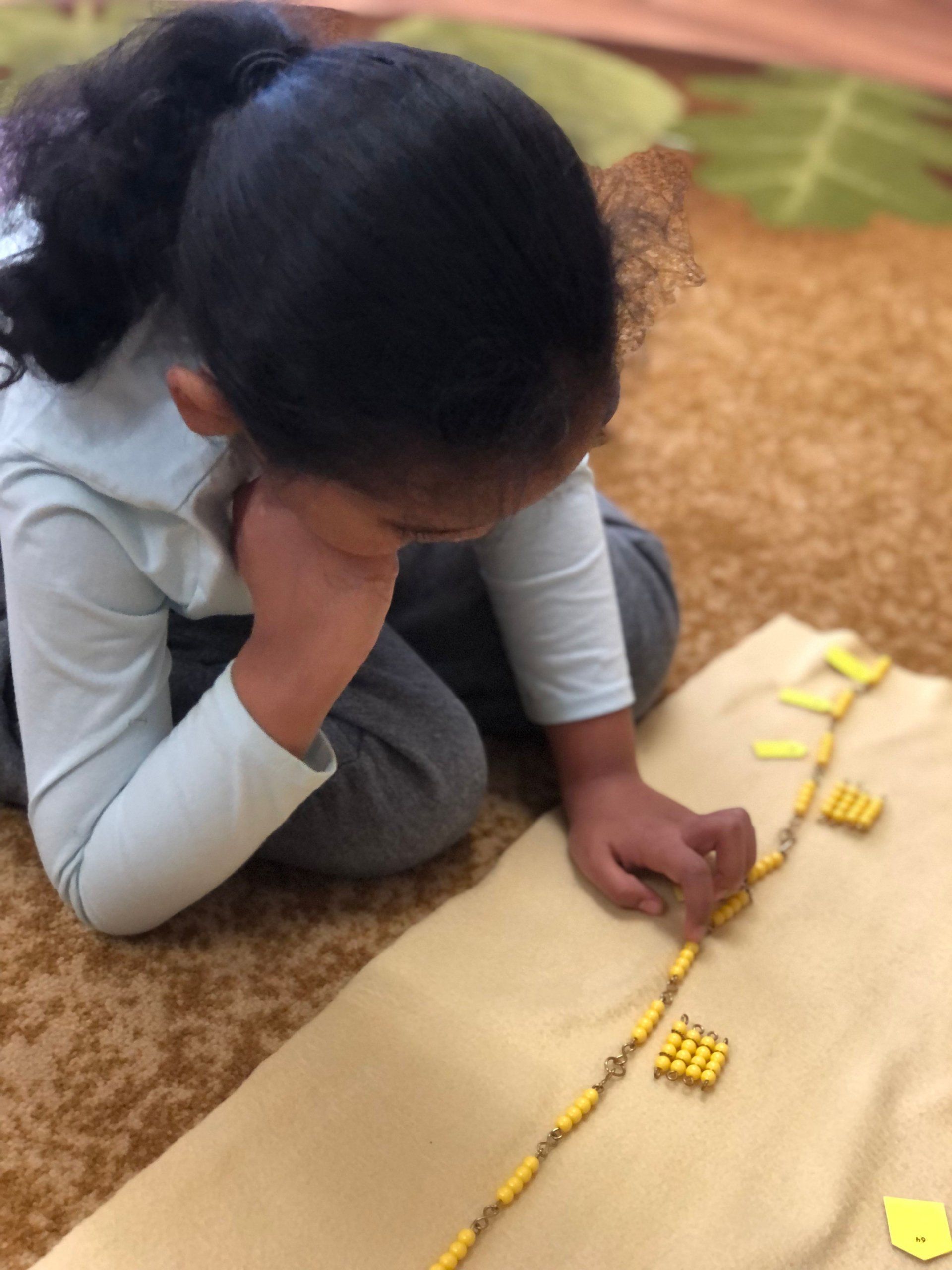

The Montessori curriculum is forever spiraling back on itself. Children are exposed to skills for the first time in very concrete ways, which is why the classrooms are stocked with so many beautiful materials. These materials help the hand teach the mind, and learning first in this physical way helps make important connections in the brain.

The concrete lessons are repeated in new ways, each time moving further toward abstract concepts. By the time the spring of the kindergarten year rolls around, children are finally solidifying so many of the ideas and skills they’ve been practicing for years.

Learn More & Come see for yourself!

On January 27, 2023 from 4 to 6pm there will be a FREE information session on what to expect in kindergarten and elementary school at CTMS. Childcare and dinner will be provided, learn more and register here: www.childrenstree.org/workshops.

One of the best ways to truly understand how a Montessori classroom works is to come in and observe. We encourage you to make an appointment to sit in a classroom and watch the children in action. Keep an eye on those kindergartners - you will be amazed at what you see!

Subscribe to our Blog

You might also like