Independence: The Foundation of Freedom

In order to be truly free, we need to be able to make our own choices, which means having the skills and abilities to then act upon our choices. Without independence, we can’t truly be free.

As children’s independence grows, so does their opportunity for freedom. They have more choices available and more to consider. The freedom children experience in our prepared learning environments is directly related to their independence. Over multiple years in their classrooms, children feel like masters of their environment and younger children look up to them as if they have superpowers.

In order for children to develop this freedom and independence, we make sure that the following opportunities are present in our classrooms:

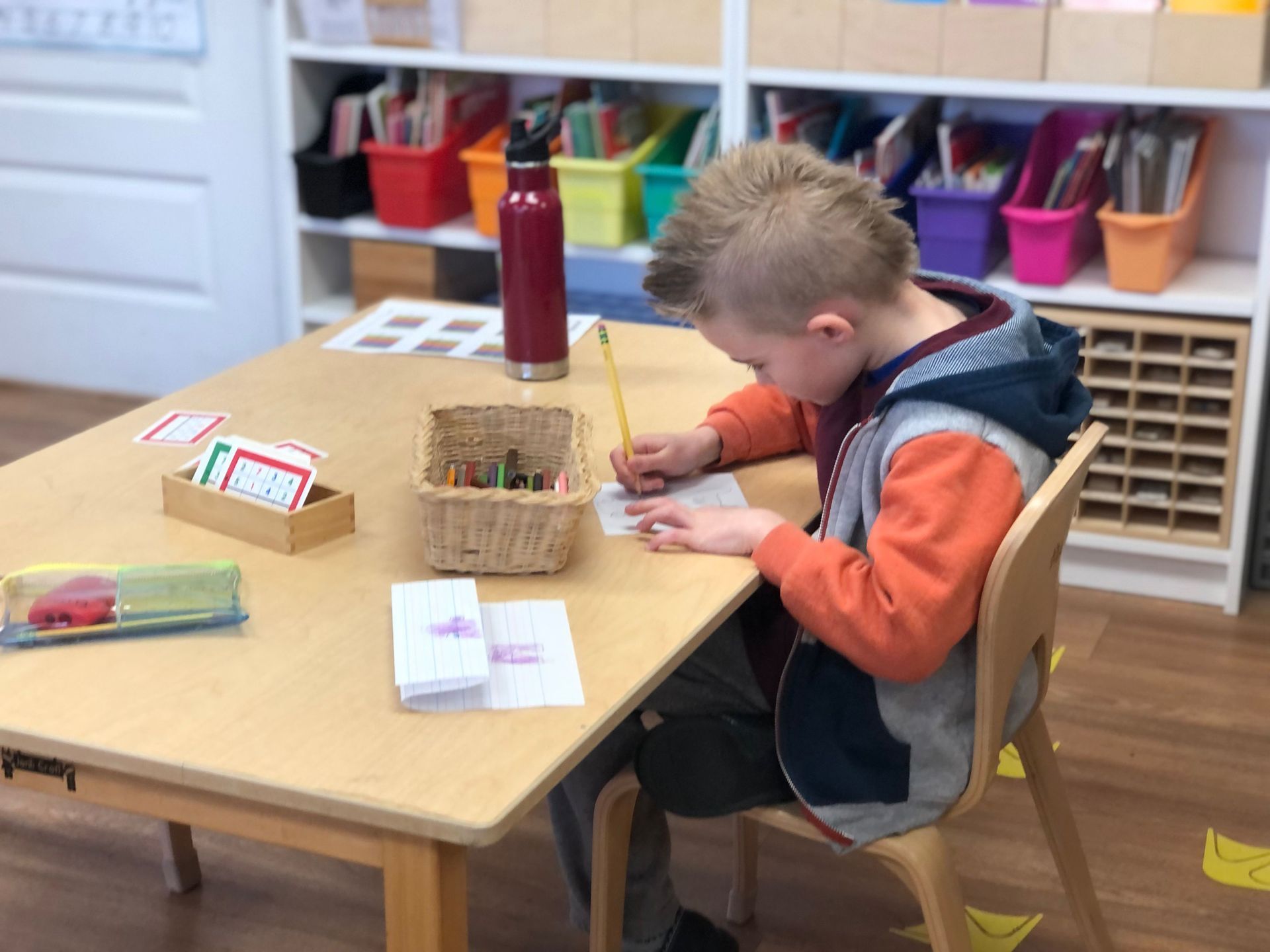

To Choose Their Own Activity

Even at a young age, children have ideas of what they want and don’t want to do. This independence will only increase when children have opportunities to make decisions. In Montessori classrooms, we provide opportunities to make choices, but it is not a free-for-all!

The classroom is set up with a variety of activities designed to meet developmental needs. Children are free to choose any material they have been shown or that they have the ability to do. Thus, children must have the skill before being able to choose.

To build this ability to make a choice, we start by offering children choices about very simple things. When an activity has two parts, we might ask: “Would you like to carry the box or the tray?” Then we give another opportunity to make a choice: “Lovely! You may carry the tray to any table that you choose.”

Over time children develop the ability to make increasingly more complex choices and they build the skills that allow them more options in their learning environment.

To Work Without Interruption

Once children choose an activity, they are free to do it for as long as they like without anyone else (adult or child) interfering with their work. In this way, we protect children’s focus and concentration. As a bonus, because the materials are self-correcting, children don’t need an adult for validation.

The adults in Montessori classrooms work to protect children who are actively engaged in purposeful activity from interruption (even if this is a three-year-old washing a table and water is pouring off the table!). If children get interrupted a lot, their concentration becomes broken which can result in them not wanting to take risks or engage with challenging learning material.

The experience of being interrupted can happen a lot to children. They try to start doing something and someone comes along and stops them or finishes it for them. Yet children need to be able to deeply dive into activity in order to develop concentration and focus.

To Move Freely

Children are free to move about the classroom. Rather than having an assigned table or workspace, they can choose to work where they want and also with whom they want. They have the liberty to get up and move, get a drink when thirsty, or go to the bathroom when needed. If there is a group activity in the classroom, children are even free to choose whether or not they want to participate.

To Communicate With Others

Children also have the freedom to communicate. They can speak to whomever they want and when they want, as long as it is not disturbing their own or others’ work. This freedom is a gift to children who are often asked to be quiet and not to talk. Children in our learning environments have the freedom to speak and the ability to be heard, which means that the adults in the classroom make it a priority to be respectful when children want to communicate something.

To Work at Their Own Pace

Unlike in traditional environments where children move together along the same path (this half hour is story time, this is math time, etc.), Montessori children have the freedom to work at their own pace. To facilitate this, our schedule is specifically designed to offer large blocks of uninterrupted time so children have the freedom to spend the time they need on the activities they choose.

Working with learning materials is how children are developing themselves. They need time to reflect and integrate what they are learning. Therefore, children also need to be able to repeat an action as often and as long as they would like to do so. When children are new to Montessori classrooms, we sometimes need to let them know about the opportunity to work at their own pace and rhythm by reminding them, “You can do this for as long as you like!”

Limits

In order to support this foundation of freedom, Montessori classrooms have a few basic limits that support independence. In addition to ensuring that children aren’t distracted or interrupted in their work, we help children learn that materials can only be taken off the shelf and must be returned to their proper place on the shelf. These basic rules are clear social signals to children as to when a material is available for use: when a material is on the shelf it is available, and when the material is not on the shelf, it is not available.

Children are also part of restoring materials so that they are ready in their proper place. In the process of making the activity beautiful for the next person, children learn how to replace wet towels with dry towels, how to dry drips of water off a tray, or how to replace anything that was consumable. When the materials are restored and returned to their proper place on the shelf, then children can access the materials independently.

Development of Independence & Freedom

As children gain skills and abilities, their independence increases and so do their choices. Activities are available and ready for use so that children are not dependent upon anyone to get things for them. Children can choose where they do their work. The lessons we offer are designed to provide just enough information for children to continue the activity independently. We offer these liberties in harmony with children’s skills, abilities, and level of independence so they can experience a variety of freedoms in their learning community.

Curious about how this all works? Schedule a tour to see how independence and freedom are interconnected! https://www.childrenstree.org/schedule-tour

Subscribe to our Blog

You might also like